Agentic search applications can feel magical, right up until the moment your data changes. The model may speak with confidence, but the context it retrieves from your source data may be stale. In production, data freshness can be the difference between an agent you trust and one you constantly second-guess. When it comes to building reliable AI systems, it all begins with the data.

In an earlier post , we discussed how multimodality is more than just a content label (text, images, video, or audio) – it’s also about how the data is stored, accessed, and used over time. We discussed the key features of LanceDB that enable it to be used as a multimodal data storage layer for AI at petabyte scale.

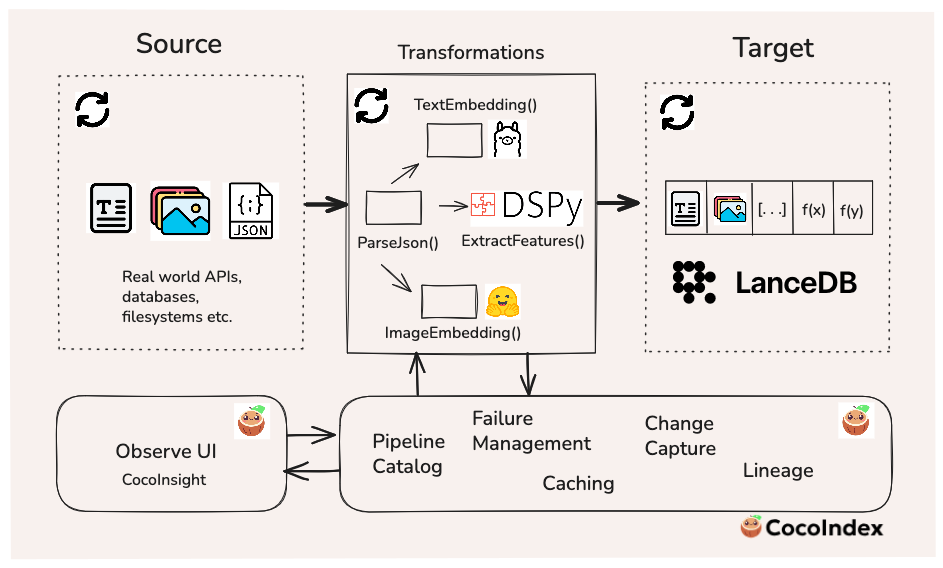

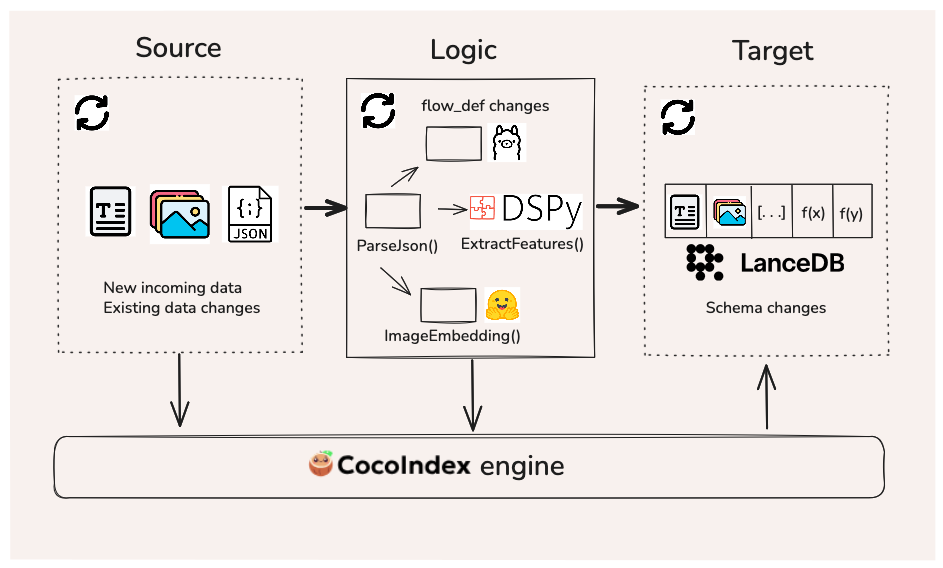

In this post, we’ll demonstrate how to use LanceDB with CocoIndex , an incremental data transformation framework that keeps source data and target data in sync when the source or the underlying code logic changes. CocoIndex continuously maintains the freshness of both schema and data in the target over time. Instead of writing custom scripts to create, insert, update, or delete data in your targets, CocoIndex manages the data flow from the sources to the targets and all the transformations in between.

Because some of the transformations involve LLMs, we’ll also use DSPy : the framework for programming, not prompting LLMs. DSPy lets you declaratively specify tasks for LLMs via signatures – instead of fiddling with brittle prompt strings, you define the input/output types and the task via the signature, and DSPy manages the LLM interactions to extract structured outputs as new features.

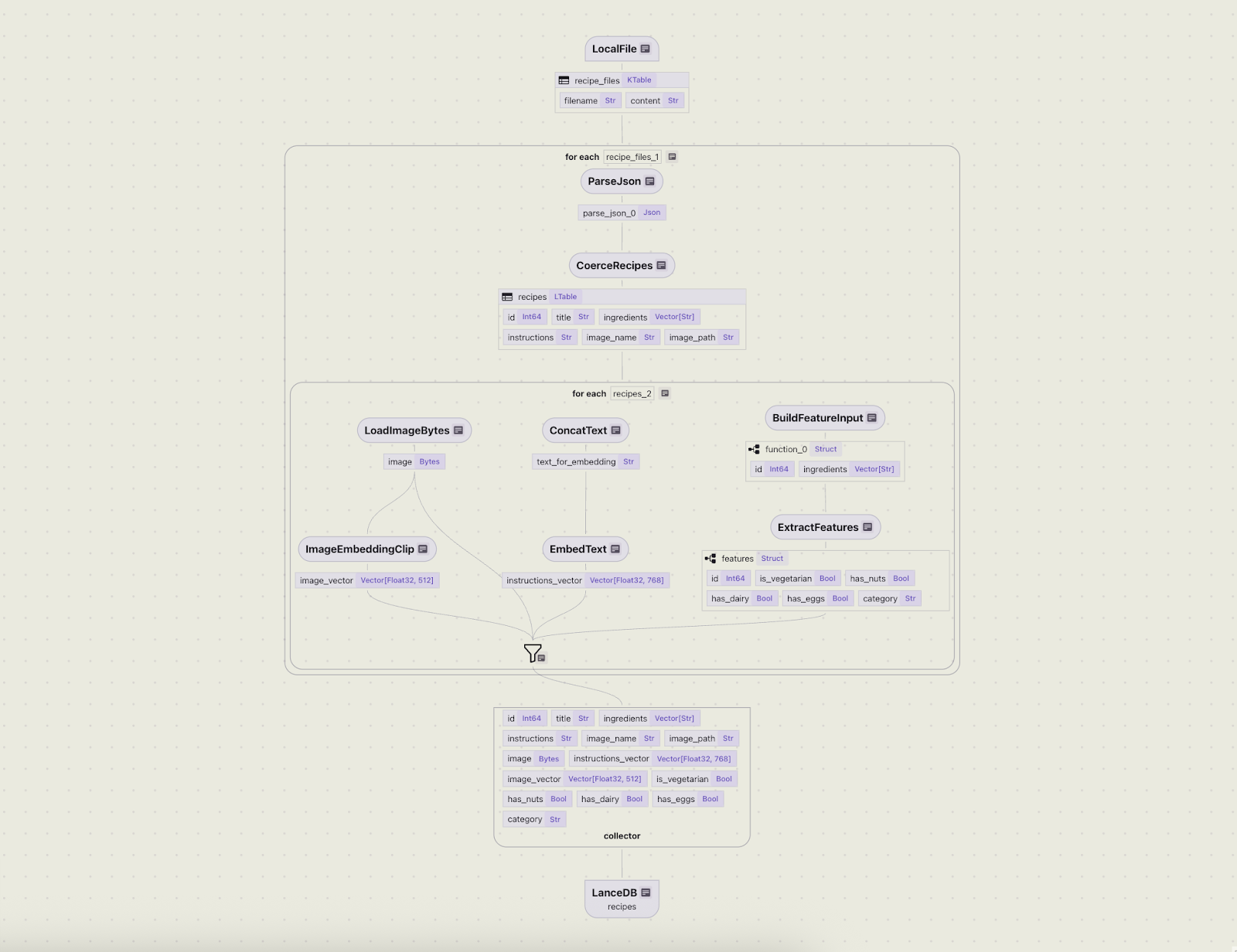

High-level summary of what’s covered in this post

The main goal of this post is to demonstrate how to build an indexing flow in CocoIndex to persist a multimodal dataset (text + images) in LanceDB. A flow is incremental, meaning that the incoming data is processed in real time, and the CocoIndex engine continually monitors the source and flow logic for updates. We then run a second-stage flow update in CocoIndex, where we update the target data by enriching it with new features extracted by an LLM, using DSPy.

Keeping the data fresh means that it can be leveraged more reliably for downstream tasks like search or analytics by humans or agents. The following sections will dive into the technical and implementation details, but the diagram below summarizes where each tool sits in the workflow.

Problem statement

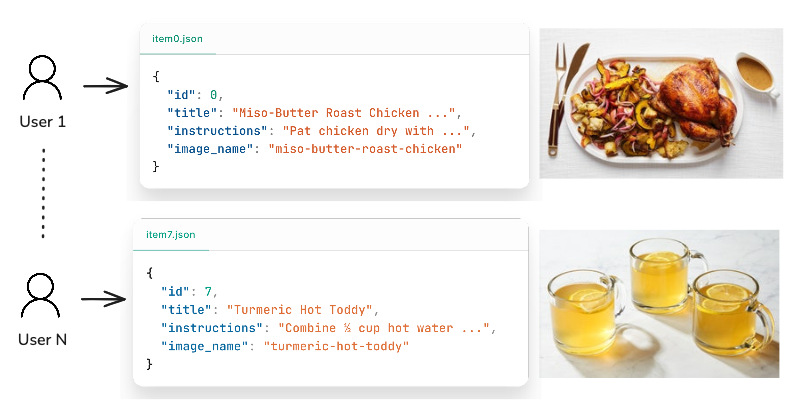

Let’s consider this scenario: you have an application where users can submit recipes of food or drinks they prepared (including photos), and you want to manage and query this multimodal data over time. In these settings, you typically don’t begin with millions of records — the dataset grows gradually as users contribute new creations. The overall volume and velocity of incoming data isn’t massive, though there may be occasional spikes.

What does matter, however, is freshness. End users expect to see the latest results show up in search and recommendation systems immediately — not hours or days later. Any delay in indexing or updating the search results can translate directly into user frustration and churn.

And in the AI-agent era, this requirement becomes even more crucial. Many agentic systems need to make autonomous decisions in dynamic environments. To act intelligently, they must rely on continuous updates as the data arrives. Stale indexes lead to irrelevant outputs, broken loops, and degraded user experience.

Incremental processing is a technique that processes only new or changed data (deltas) continuously, rather than batch-processing large amounts of data at once. This is the main goal of the pipeline we’ll build.

Why LanceDB?

This naturally raises the question: what would make for a good storage target? For applications like this one, where you know you have multimodal data coming in at scale, you may want a storage layer that can keep the actual multimodal data (images or large blobs), the embeddings, and the metadata co-located in one place – this makes the dataset easier to govern, share, and reuse. LanceDB is a good fit for both search and analytics workloads, supporting disk-native indexes and data versioning out-of-the-box.

And as you iterate and enrich the data over time – e.g., you run a DSPy function to extract new features using an LLM – you can add new columns and backfill them in LanceDB without rewriting the whole table. This ability to “grow your tables in two dimensions” is exactly what you want when your pipeline is continuously refreshing data and your team is regularly adding new features.

Why CocoIndex?

As a data practitioner, you likely find yourself writing custom scripts to manage workflows for every new data source, while also writing extra scripts/hooks to track state: “Did this specific record change since the last run? Do I need to re-run the embedding model? If I update the metadata, do I have to rewrite the entire table”? As the number of data sources you work with grows, this can become a tedious process with brittle pipelines that may fail to keep your data fresh for your downstream applications.

CocoIndex is a data transformation framework for AI that solves the freshness problem by letting you define a declarative flow for data transformation, keeping your target (LanceDB in this case) up to date with your latest sources (e.g., JSON files or REST APIs), and applying the latest transformation logic on an incremental basis as changes occur in real time. This guarantees that if a particular record changes, only that record passes through the flow.

CocoIndex supports LanceDB as a built-in target . This makes it simple to store your data in LanceDB while managing your incremental processing workloads in CocoIndex. You can easily install both tools, which are open-source, via a single command as follows:

pip install "cocoindex[lancedb]"Dataset

We’ll be using a food ingredients and recipes dataset from Kaggle for this post. It contains 13,000+ recipes of food/drinks (and importantly, images of each item, making it a multimodal dataset) scraped from the Epicurious website. This dataset aligns well with our hypothetical mobile or web app use case mentioned above, where individual users enter their recipes along with photos of their creations.

To simulate a “push API” where data incrementally enters the system in real time, we provide a script that generates an on-demand subset of the recipe data as JSON files, along with the corresponding image file for that recipe item. This is the data that CocoIndex will use and monitor as its “source”. Note that CocoIndex supports an arbitrary number of built-in and custom sources of data, so it’s not limited to just files on the local filesystem.

Schema and embedding model definition

Because our goal is to demonstrate an incremental pipeline for maintaining data freshness, rather than directly ingesting the raw data into LanceDB via a batch job, we’ll handle data ingestion via a declarative indexing flow in CocoIndex.

Define Pydantic models

We’ll start by defining a RecipeInput Pydantic model that contains the type information for each field within a recipe record. The id field is non-nullable and will be used as the primary key identifier in the data ingestion pipeline.

from pydantic import BaseModel

class RecipeInput(BaseModel):

id: int

title: str | None = None

ingredients: list[str] | None = None

instructions: str | None = None

image_name: str | None = None

image_path: str | None = NoneLoad embedding models

For text embeddings, we’ll be using the nomic-embed-text model via

Ollama

. This is a great open-source text embedding model from Nomic that runs on CPU and is fast enough for our local tests. First, pull the model from Ollama to your local machine:

ollama pull nomic-embed-textFor image embeddings, we’ll use the

CLIP

model from the Hugging Face transformers library, also fully open-source. To avoid reloading the model every time it’s invoked, we can wrap it in a @functools.cache() decorator.

@functools.cache

def load_clip_model() -> tuple[CLIPModel, CLIPProcessor, torch.device]:

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

print(f"Using device: {device}")

model = CLIPModel.from_pretrained(IMAGE_MODEL_NAME)

processor = CLIPProcessor.from_pretrained(IMAGE_MODEL_NAME)

model.to(device) # type: ignore[call-arg]

model.eval()

return model, processor, deviceBuild the flow

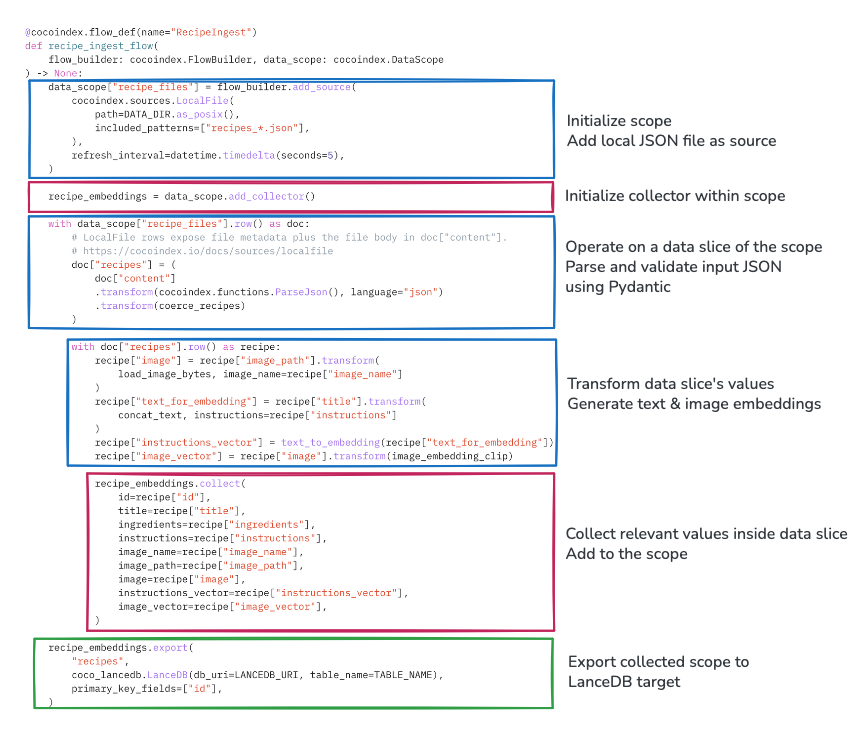

An indexing flow is a declarative definition that clearly specifies the data source and transformation steps (either as an intermediate result or the final result to be put into the target). CocoIndex requires that all data within the indexing flow uses a schema that’s known upfront, at flow definition time – this aligns well with LanceDB’s Arrow-based strictly typed philosophy, which requires that Lance tables have a known schema beforehand.

The entry point to an indexing flow is a Python function, decorated by @cocoindex.flow_def(). Any given flow is typically composed of the following components:

- Data scope: Defines all data accessible within the flow, including raw source data and transformed data. You can add any number of sources to the scope, and access slices of the data as required to transform the data within the scope.

- Data collector: Collects data and adds it to the scope once the transformations are run.

- Data export: Writes the transformed and collected data to the target (in our case, LanceDB).

The diagram below clarifies these concepts and makes them more concrete for our recipe example.

Inside the function, the flow is initialized using a flow_builder, where we add the data source — JSON records from the local filesystem that emulate a real-world API-like source.

The initial transformations occurring on the data during ingestion time are text embedding generation (on the title + instructions text fields), and image embedding generation (on the images of the food/drink items).

When invoking the flow builder in CocoIndex, you have the option of setting a refresh interval . In this example, it’s set to 5 seconds, meaning that CocoIndex will track changes to the source and the target in near-real-time.

import cocoindex

@cocoindex.flow_def(name="RecipeIngest")

def recipe_ingest_flow(

flow_builder: cocoindex.FlowBuilder, data_scope: cocoindex.DataScope

) -> None:

data_scope["recipe_files"] = flow_builder.add_source(

cocoindex.sources.LocalFile(

path=DATA_DIR.as_posix(),

included_patterns=["recipes_*.json"],

),

refresh_interval=datetime.timedelta(seconds=5),

)Transformations within a flow’s data scope are defined as

custom functions

in CocoIndex. For brevity, not all functions used in this demo are shown here, but an example function that concatenates the title and instructions fields (decorated by @cocoindex.op.function()), and how to declare it in the flow, are shown below.

@cocoindex.op.function()

def concat_text(title: str | None, instructions: str | None) -> str:

"""

Concatenate the text for the `title` and `instructions` field

"""

parts: list[str] = []

if title:

parts.append(title.strip())

if instructions:

parts.append(instructions.strip())

return "\n\n".join(parts)

# Use the custom function in a flow

@cocoindex.flow_def(name="RecipeIngest")

def recipe_ingest_flow(

flow_builder: cocoindex.FlowBuilder, data_scope: cocoindex.DataScope

) -> None:

# ... Define data scope

with data_scope["recipe_files"].row() as doc:

with doc["recipes"].row() as recipe:

# .. Do stuff here

# Run text concatenation transforms

recipe["text_for_embedding"] = recipe["title"].transform(

concat_text, instructions=recipe["instructions"]

)

# .. Do more transformations as required here

# Define data export target

recipe_embeddings.export(

"recipes",

coco_lancedb.LanceDB(

db_uri=LANCEDB_URI,

table_name=TABLE_NAME,

num_transactions_before_optimize=50, # No. of transactions before optimizing table

)

primary_key_fields=["id"],

)Once the transformations are declared, the collector gathers the relevant data within scope and specifies the export target as LanceDB. Under the hood, CocoIndex handles all the necessary type conversions from Python/Pydantic types to the PyArrow types that LanceDB requires.

num_transactions_before_optimize parameter in the target spec for LanceDB.

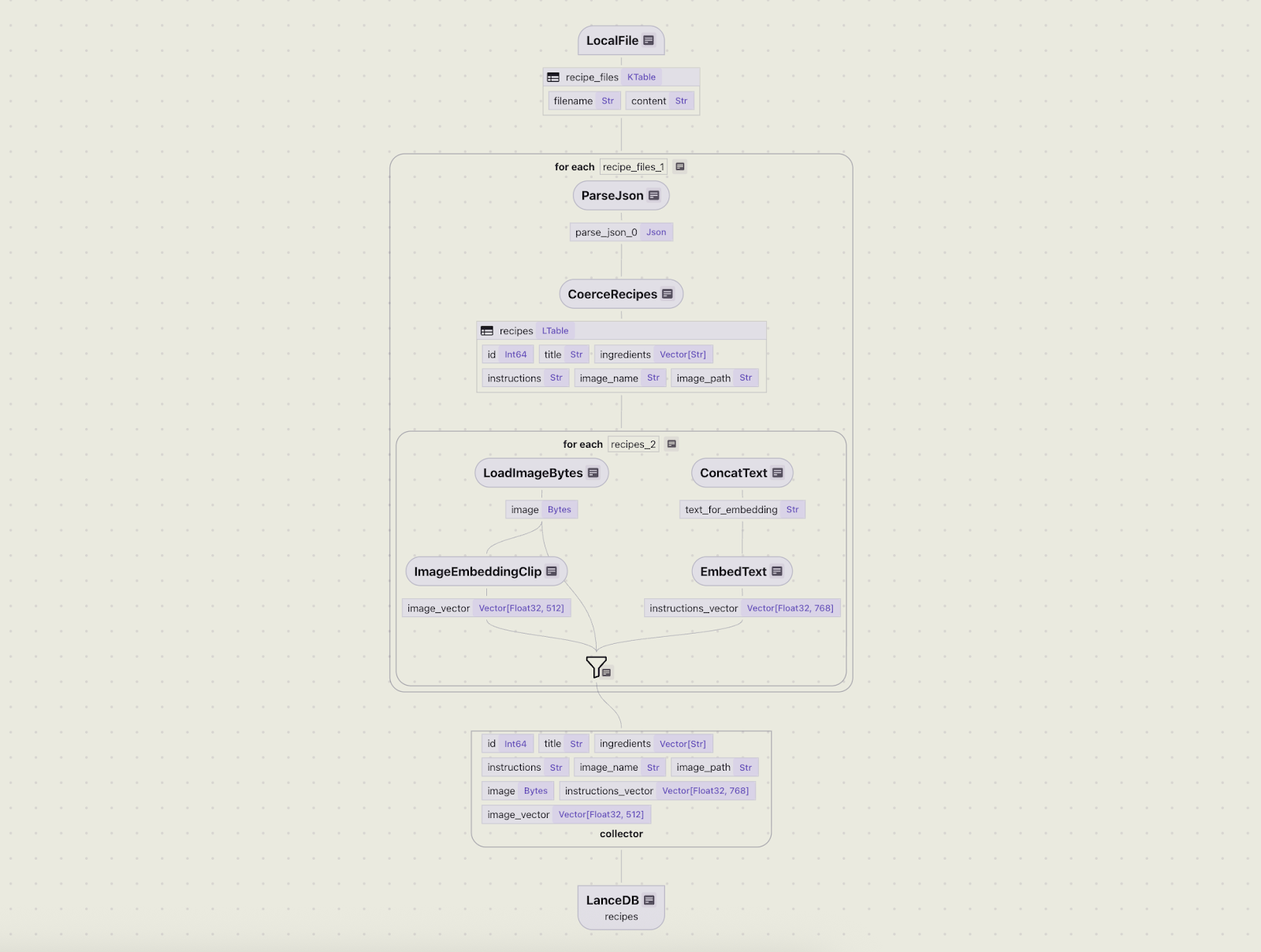

Visualize the flow

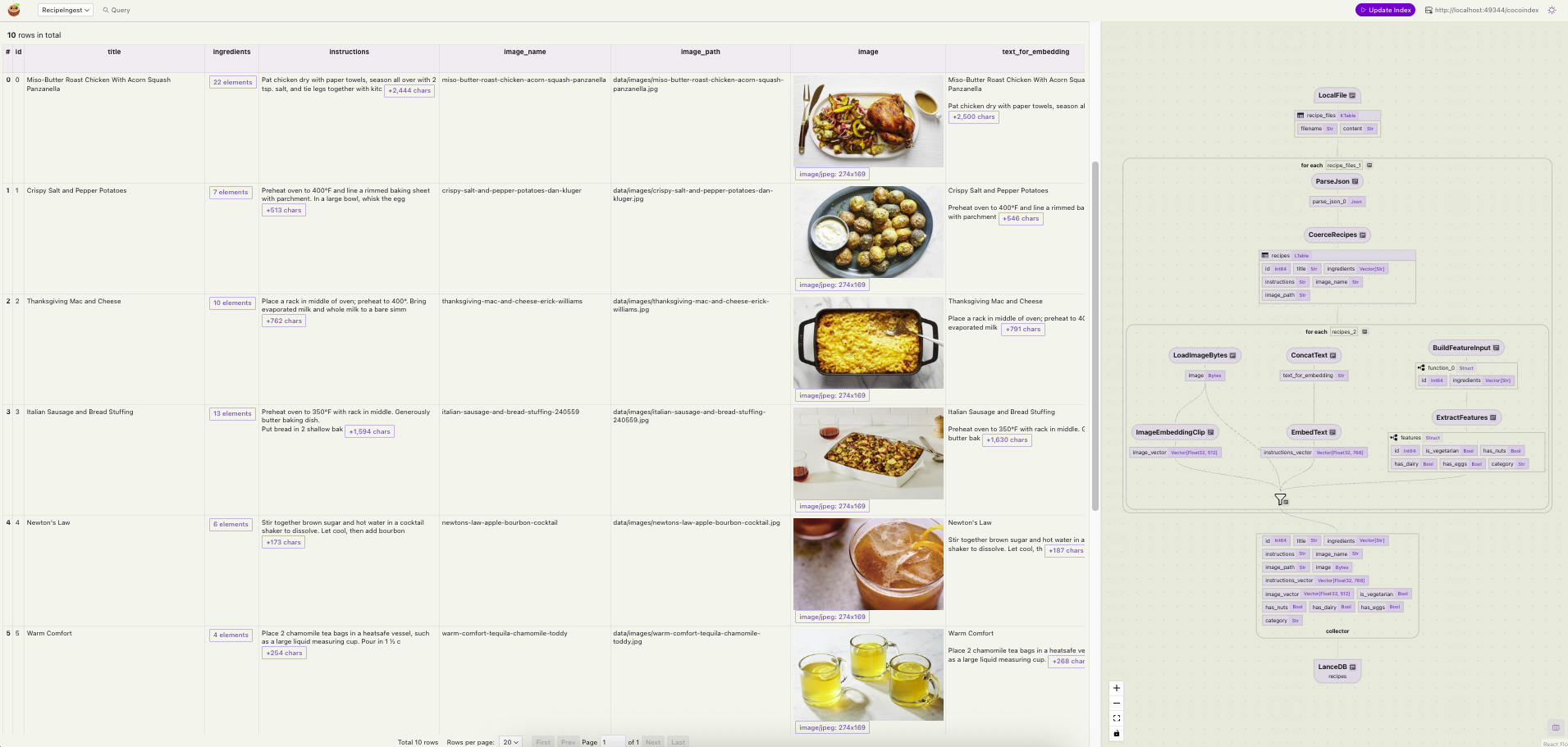

You can better understand the flow hierarchy and interactively query the data using CocoInsight . The following command runs a frontend server for the UI, accessible at cocoindex.io/cocoinsight :

cocoindex server -ci mainThe flow diagram below concisely describes the hierarchy of operations that will be performed by the flow once a change occurs.

Operate the flow

Once the initial flow has been defined, we can put it to the test! We simulate some fresh, incoming data in an empty directory by running the data generation script for the first 5 records.

python data_generator.py --start 0 --end 5This will write a JSON file with 5 records and 5 images to a local directory data/ that’s being monitored as a source.

We’ll first bring up a Postgres database that serves as CocoIndex’s internal storage – because an indexing flow is long-lived, this is where CocoIndex stores intermediate data to keep track of state. The following command can be used to launch Postgres inside a Docker container:

docker compose -f <(curl -L https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cocoindex-io/cocoindex/refs/heads/main/dev/postgres.yaml) upTo run a one-time flow, run the following command in a terminal:

cocoindex update mainAlternatively, you can run the flow in “live” mode with the -L flag.

cocoindex update main -LThis will keep a long-lived CLI process alive (with full logging), tracking changes to the source/target at the frequency defined in the flow. Every 5 seconds, if the internal server in CocoIndex identifies changes to the source or the logic, it will automatically rerun the flow.

Because CocoIndex is an incremental processing framework, only those records that changed (or are brand new) will pass through the flow.

Manage updates

In the real world, both data and use cases continually evolve. Consider this common scenario — a data scientist needs to enrich the recipe dataset with features so that they can run aggregation queries and calculate statistics. For example: “How many recipes contain dairy?”, or “What fraction of recipes in the catalog are beverages?” These questions are not a good fit for vector search, as they involve exact matches on specific boolean or categorical values, followed by counting.

To answer a broader variety of questions, we need to enrich the existing data in LanceDB by extracting features from images/text and adding them as new columns to the table.

Define a DSPy pipeline

We’ll define a DSPy signature that can handle a range of feature extractions in a single LLM API call, and use the CocoIndex flow to update the data in LanceDB.

import dspy

class FeatureExtractor(dspy.Signature):

"""

Given a recipe's list of ingredients, extract the required features.

- Treat eggs as vegetarian and fish as non-vegetarian.

- Nuts include any kind of tree nuts, peanuts, and ground nuts.

- Dairy includes milk, cheese, butter, yogurt, or other products made from animal milk.

"""

id: int = dspy.InputField()

ingredients: list[str] = dspy.InputField()

is_vegetarian: bool = dspy.OutputField()

has_nuts: bool = dspy.OutputField()

has_dairy: bool = dspy.OutputField()

has_eggs: bool = dspy.OutputField()

category: Literal["food", "beverage"] = dspy.OutputField()Signatures are a declarative way to specify LLM interactions in DSPy. In this signature, we’re declaring the user instructions via its docstring — this will be included in the structured prompt that DSPy constructs under the hood. The main goal in this signature is to extract the following features from the list of ingredients in a recipe:

- Is it vegetarian?

- Does it have nuts?

- Does it contain dairy?

- Does it contain eggs?

- Is the recipe a food or a beverage?

Note how the signature also explicitly specifies which fields are inputs/outputs, as well as their data types (either built-in Python types or Pydantic models). Signatures are more than just templated prompts — they combine natural language and a type system and formulate a structured prompt under the hood, helping the LLM better adhere to the task at hand.

The signature is passed to a module , which is the main unit of a DSPy program. The module is what actually invokes the LLM.

class Extract(dspy.Module):

"""

DSPy module to extract recipe features using the FeatureExtractor signature.

"""

def __init__(self):

self.extractor = dspy.Predict(FeatureExtractor)

def forward(self, recipe: RecipeFeatureInput):

return self.extractor(id=recipe.id, ingredients=recipe.ingredients)

async def aforward(self, recipe: RecipeFeatureInput):

"""Async version of forward"""

return await self.extractor.acall(id=recipe.id, ingredients=recipe.ingredients)The module is instantiated with one or more signatures that define the task for the LLM. The forward method is a special method marked as “optimizable” by DSPy, and aforward is its async variant. It invokes the LLM via the module’s __call__ method and manages the prompt based on the given signature.

The module returns a set of fields as requested in the signature — these are the new features we want to add to our LanceDB table.

Update CocoIndex flow

Now that we’ve defined the DSPy utilities, we can use them to update the flow logic in CocoIndex. First, we extend the Pydantic schemas for the new features. These are transformed under the hood by CocoIndex to a PyArrow schema, so the LanceDB schema gets updated accordingly in the flow.

class RecipeFeatureInput(BaseModel):

id: int

ingredients: list[str] | None = None

class RecipeFeatureOutput(BaseModel):

id: int

is_vegetarian: bool | None = None

has_nuts: bool | None = None

has_dairy: bool | None = None

has_eggs: bool | None = None

category: str | None = NoneNext, we define extract_features as a custom CocoIndex function that asynchronously applies the DSPy pipeline on an incoming record, extracting all the features for that record in a single LLM API call.

@cocoindex.op.function()

async def extract_features(recipe: RecipeFeatureInput) -> RecipeFeatureOutput:

extractor = Extract()

prediction = await extractor.aforward(recipe=recipe)

if prediction is None:

return RecipeFeatureOutput(id=recipe.id)

return RecipeFeatureOutput(

id=recipe.id,

is_vegetarian=prediction.get("is_vegetarian"),

has_nuts=prediction.get("has_nuts"),

has_dairy=prediction.get("has_dairy"),

has_eggs=prediction.get("has_eggs"),

category=prediction.get("category"),

)This function can now be used in our flow definition to run the feature transformation. We also update the collector to gather the features within scope and update the LanceDB target with the new data.

# Update existing flow

@cocoindex.flow_def(name="RecipeIngest")

def recipe_ingest_flow(

flow_builder: cocoindex.FlowBuilder, data_scope: cocoindex.DataScope

) -> None:

# ... Existing data scope

with data_scope["recipe_files"].row() as doc:

# ... Existing top-level transforms

with doc["recipes"].row() as recipe:

# ... Existing slice-level transforms

# Call feature extraction function

recipe["features"] = feature_input.transform(extract_features_batch)

# Update collector

recipe_embeddings.collect(

id=recipe["id"],

title=recipe["title"],

ingredients=recipe["ingredients"],

instructions=recipe["instructions"],

image_name=recipe["image_name"],

image_path=recipe["image_path"],

image=recipe["image"],

instructions_vector=recipe["instructions_vector"],

image_vector=recipe["image_vector"],

is_vegetarian=recipe["features"]["is_vegetarian"],

has_nuts=recipe["features"]["has_nuts"],

has_dairy=recipe["features"]["has_dairy"],

has_eggs=recipe["features"]["has_eggs"],

category=recipe["features"]["category"],

)

recipe_embeddings.export(

"recipes",

coco_lancedb.LanceDB(db_uri=LANCEDB_URI, table_name=TABLE_NAME),

primary_key_fields=["id"],

)CocoIndex is responsible for propagating the schema changes to LanceDB via the export target. Once this is saved, we can run the command cocoindex server -ci main, and we can see that the flow diagram is updated in the CocoInsight UI to account for the new feature extraction logic.

primary_key_fields parameter, shown in the export method above. Rather than inserting duplicate records, it runs the merge_insert command (which is basically an upsert in LanceDB). If you’re interested in digging deeper, you can look at the

mutate

method of the LanceDB target in CocoIndex’s codebase.

Operate the updated flow

We’re now ready to put the updated flow logic to the test! When the main.py file that contains the flow is saved, CocoIndex identifies that there’s a discrepancy between the LanceDB schema and the flow’s current state, so it runs the flow and propagates these changes to the target.

The role that CocoIndex plays here is twofold: it observes changes to the source or the logic, and applies changes to the target. The following diagram shows the information flow between each component of the system.

What constitutes “stale” data?

In the real world, there are multiple scenarios in which data can become stale:

- New rows/files added to the source: The existing data may be untouched, but the new data must be transformed and added to the target where required. CocoIndex runs per-row logic to process and insert new rows into the target.

- Existing rows/files deleted from the source: A particular record (or a small part of it) is deleted from the source, and it must be refreshed in the target. CocoIndex deletes rows associated with the deleted source row from the target.

- Existing rows/files modified in the source: CocoIndex runs per-row logic to reprocess and insert/update/delete rows in the target if there’s any change to the output rows for the target after the source change (this is logically the same as

source_row_delete+source_row_add, but unchanged target rows won’t be touched). - Logic change (no target schema change): The transformation logic gets updated in the flow definition. For example, you might update the embedding model, which needs to be reflected in the target data. CocoIndex reprocesses all source rows (“backfills”) in the target, reusing cached transformation results where possible (e.g. the DSPy pipeline was unchanged, so we don’t need to rerun that part).

- Schema change (introduced by logic change): The logic change involves a schema change. For example, the DSPy pipeline is added that extracts a set of features that need to be backfilled as new columns in the LanceDB target. CocoIndex updates the target table schema, adds the new columns and reprocesses all source rows. Once again, cached transformation results may be reused where possible, for existing unchanged columns.

Add new source data

To simulate a fresh batch of data coming in, we can run the data generation command on a different set of IDs (5–10 in this case).

python data_generator.py --start 5 --end 10This will add 5 new records containing recipe data to the data/ directory, which is being watched by CocoIndex.

✅ RecipeIngest.recipe_files (interval update):No input data [elapsed: 0.000s]

✅ RecipeIngest.recipe_files (interval update):No input data [elapsed: 0.000s]

✅ RecipeIngest.recipe_files (interval update):▕████████████████████████████████████████▏1/1 source rows: 1 added [elapsed: 1.897s]Each time a new JSON file is added to the source directory, the recipe ingestion pipeline in CocoIndex runs, and the number of rows in the dataset is incremented by one.

Update existing source data

Later, a developer or an application process might modify the source data of a previously added recipe, changing its ingredients and instructions. In the example below for the recipe “Turmeric Hot Toddy”, the Amontillado sherry ingredient is replaced with Vermouth, and the file is saved.

{

"id": 7,

"title": "Turmeric Hot Toddy",

"ingredients": [

"...",

"1 \u00bd oz. Amontillado sherry",

"...",

],

"instructions": "For the turmeric syrup, ...",

"image_name": "turmeric-hot-toddy-claire-sprouse",

"image_path": "data/images/turmeric-hot-toddy-claire-sprouse.jpg"

}Because the CocoIndex engine watches all source files and their contents, any change to them or the flow logic in main.py is considered a trigger to run an update. As a maintainer of the recipe application, you don’t need to write any custom batch scripts to add, delete, or modify data in the target manually. The flow will handle syncing and run only on the source data that changed.

Here’s what the CLI log looks like in such a scenario. One of the existing source files has been updated, while the other two had no changes.

✅ RecipeIngest.recipe_files (interval update):▕████████████████████████████████████████▏3/3 source rows: 1 updated, 2 no change [elapsed: 1.265s]Querying the data immediately reveals the updated ingredient, Vermouth, in the latest state.

{

"id": 7,

"title": "Turmeric Hot Toddy",

"ingredients": [

"...",

"1 \u00bd oz. Vermouth",

"..."

],

"instructions": "For the turmeric syrup, ...",

"image_name": "turmeric-hot-toddy-claire-sprouse",

"image_path": "data/images/turmeric-hot-toddy-claire-sprouse.jpg"

}View updated flow results

Once the update flow is done, you can visually inspect the data in the CocoInsight UI and verify that the data is present in LanceDB. The UI provides a “Query” tab so you can enter keywords to test this. Scrolling horizontally shows that our data has all the new features extracted by DSPy as new columns – Our recipe data is now fresh and ready for consumption by agents!

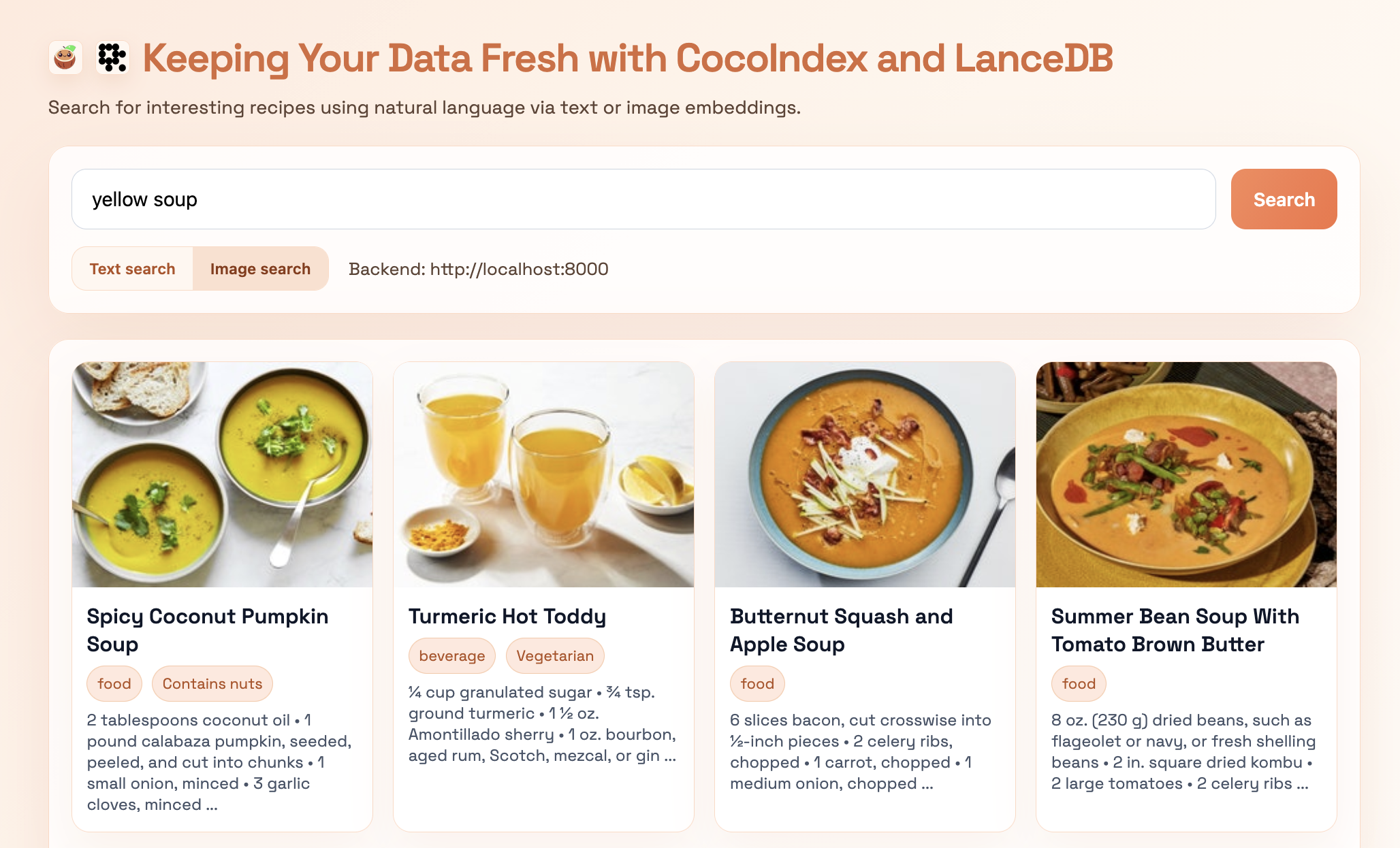

Search application demo

Let’s wrap up by building an interactive search app that retrieves relevant data from LanceDB using either text or image embeddings. We provide a docker-compose.yml file in

the repo

to run the app locally. The following command runs the frontend, which you can access in your browser.

docker compose upSimply enter a search query in natural language, pick the search mode (text or image), and hit “search”. The image below is for the query “yellow soup”. The natural language query is translated into image embedding space to retrieve the top-k most similar results by image — we can see that we get back items that look soupy (or at least, like liquids) and are yellow, which means our embeddings are doing their job!

Any new incoming data to the source directory will trigger an automatic update to the data being served in LanceDB if you run CocoIndex in “live” mode as shown earlier in this post:

cocoindex update main -LHave fun trying out the search app on your own queries!

Key takeaways

We began with a “living” recipe dataset that changes over time and built towards an end-to-end search pipeline that can keep up in real time. Let’s end with the key takeaways and a little food for thought, served fresh 🥦:

- CocoIndex is the data transformation engine: it uses declarative flows and incremental processing to keep derived artifacts, including embeddings and feature columns, synchronized between the source and the target. It provides lineage out of the box, observes state (before and after transformation) – helping you bring together multiple data sources and targets – solving the pain of managing data freshness.

- DSPy helps make working with LLMs simpler: signatures make LLM-powered feature extraction feel like a programmatic exercise (rather than brittle prompt engineering). It also comes with prompt optimization capabilities out of the box, helping you discover (via algorithms) the best prompts for the task at hand.

- LanceDB is the scalable serving layer for multimodal data, and we only scratched the surface here, using basic similarity search for retrieval. With larger datasets, you’d typically add vector and full-text search indexes to keep retrieval latency low (see the indexing docs ).

If you want to improve this search app to better serve users downstream, a few additions would go a long way:

- Hybrid retrieval + reranking: run full-text search (FTS), text-embedding search, and image search concurrently, then rerank the union for relevance (and optionally diversity) before returning results to the agent.

- “Counting” and structured questions: once you have feature columns (e.g.,

is_vegetarian, cuisine, allergens), add a tool that answers queries like “how many recipes are vegetarian?” via filtered queries in LanceDB (see filtering without vector search ). - Agentic search: An agent loop could be used to inspect the retrieved results and decide whether the answer retrieved adequately answers the user query, and if not, attempt to retrieve the result another way. This would improve the resilience of the search app by reducing empty or inaccurate responses.

- Recipe recommendation bot: You could take things a step further with a recommendation bot: users can describe the type of dishes they want, and the agent can query the database based on features and embeddings to suggest recipes. For example, you may want to ask, “I want a quick, vegetarian dinner in under 30 minutes”, and the agent would filter on the extracted features, rank, and present relevant options. This creates a more interactive, personalized experience beyond simple search.

Conclusions

We’re at the dawn of a new era for multimodal AI, which requires modern infrastructure and tooling to help build ever more applications that will be leveraged by agents. Alongside traditional scalar data, you may come across images, PDFs, and other static assets, as well as audio and video blobs. For this recipe app, you could easily imagine adding an “upload a cooking video” feature to further improve the user experience (because it’s a lot easier to understand recipes by watching someone cook than to read their instructions).

All this means more data, coming in at a higher volume, velocity, and variety, to be processed in more ways than before, feeding an ever-growing catalog of AI-enabled applications in an organization. LanceDB (via the Lance format’s native blob support ) is designed to stay performant when searching through complex heterogenous data, no matter its size or shape. When you build your retrieval layer in LanceDB, you can maintain your images, text, video, and more in one place – so both humans and agents can search effectively across them.

In a production environment, these three truths are ever-present: a) data is never static, b) user logic is always evolving, and c) project requirements are continually changing as new data becomes available. When you build your data pipelines in CocoIndex, you incrementally (re)process only what’s needed, as changes occur. Fresh data becomes queryable immediately, new code paths don’t trigger massive backfills, and the system avoids the heavy pipeline maintenance that’s typically required to keep everything consistent. This keeps your retrieval layer — and the agents relying on it — continuously up-to-date, stable, and robust.

From here, the menu is yours!

Code

If you want to try building the pipeline yourself, the code to reproduce the examples in this post is available on GitHub .

Links

The relevant links for the LanceDB and CocoIndex communities are shown below (don’t forget to give them each a star ⭐️ on GitHub).

| Project | Discord |

|---|---|

| LanceDB: github.com/lancedb/lancedb | Join here |

| CocoIndex: github.com/cocoindex-io/cocoindex/ | Join here |