The fundamental characteristic of a table format that makes it more than a file format is that it defines how data is assembled. When you look at the architecture diagram of well-known table formats like Iceberg or Lance , you see a hierarchical structure with path references. A top-level metadata file (a metadata JSON for Iceberg, a log + checkpoint in Delta, or a manifest in Lance) links together all the files that comprise the table.

Those arrows in the architecture diagram may look mundane – it’s just “paths” right? But should paths be absolute or relative? Should the format enforce directory conventions or allow files to be put anywhere? These decisions have profound implications for the portability and operational complexity of the format, when applied at petabyte scale.

Those questions became very real when Uber’s AI infrastructure team came to us with a production requirement: distribute a single Lance dataset across multiple S3 buckets to scale throughput, while preserving the portability benefits of relative paths.

Having worked on Apache Iceberg, Delta Lake, and now Lance, I’ve observed this debate play out across formats – and had the chance to help design solutions more than once. This post recaps that evolution and then introduces Lance’s latest step forward: a multi-base path model that, in my view, is the cleanest way to support multi-location storage without sacrificing portability.

The Iceberg Journey: From Absolute Paths to Relative

The original design of Apache Iceberg adopted absolute paths for file references, with a clear rationale behind the decision – absolute paths have the following advantages:

- No ambiguity: The path

s3://my-bucket/warehouse/db/table/data/00001.parquethas no alternate interpretations - Flexibility: Files can theoretically live anywhere, even outside the table root

- Simplicity: Path resolution requires no context; “what you see is what you get”

However, in 2021, the Iceberg community began in-depth discussions about supporting relative paths at the format level (see this mailing list thread ). The discussion surfaced a fundamental tension that emerged from real-world usage: absolute paths worked well for static, single-location deployments, but broke down in dynamic, multi-cloud environments. Consider what happens when during table migration. Every metadata file contains thousands (or millions) of absolute paths. Changing the storage location means rewriting every metadata and manifest file, an expensive, error-prone operation that often requires distributed processing jobs to handle such “big metadata”.

Over the last four years, discussions about this feature have repeatedly come up, with vendor-specific solutions like Amazon’s S3 bucket aliases and access points being added to address specific use cases for disaster recovery and data replication. But at the format level, there was little movement.

Finally, in late 2025, the Iceberg community began to align on a design for relative paths in v4 (see the mailing list thread ). The v4 proposal’s goal is to have zero rewrites to improve portability: when relocating a table (i.e., copying the entire table from one prefix or folder to another), no metadata files need to be modified. This is achieved by making paths without a URI scheme relative, resolving against the table location. The table location can be explicitly specified or derived from the metadata JSON file path. Additionally, the data and metadata locations can be configured to point to a different subfolder or entirely different storage systems.

The Delta Journey: From Relative Paths to Absolute

Delta Lake took the opposite approach, beginning with relative paths. When the protocol specification was first published in September 2019, the definition was as follows: “a relative path, from the root of the table, to a file that should be added to the table” (commit 43f40d7c ). This meant Delta achieved zero rewrite portability from day one: copy a table directory, and it just works.

However, in August 2021, the protocol was updated to allow absolute paths (commit 4d865949 ). The specification now reads:

path: A relative path to a data file from the root of the table or an absolute path to a file that should be added to the table.

This change laid the groundwork for features like shallow clone, introduced in December 2022 (commit b038b9d6 ). Shallow cloning creates a new table that references data files from an existing table without copying them. Because those files sit outside the new table’s root directory, absolute paths become necessary. Delta thus evolved from a purely relative model into a hybrid one – gaining flexibility, but giving up some of its original portability guarantees.

Reflections on the Design

While Iceberg (in the future V4) and Delta are good enough for the zero rewrite philosophy, I found the designs unsatisfying for a few reasons.

The false promise of flexibility

The flexibility of using absolute paths seems compelling: why constrain where files can live? In practice, that flexibility is rarely used – files almost always sit under the table’s root. And once files do span multiple locations, table maintenance gets harder: you can’t safely garbage-collect a directory if its files might be referenced elsewhere. Security features like credentials vending are also typically built around a single prefix so temporary access can be scoped narrowly. Vending credentials for one-off absolute paths across many locations is uncommon across the lakehouse stack, and even when it’s supported, it doesn’t scale gracefully as the number of distinct locations grows.

Zero rewrite, until you can’t

“Zero rewrite” is a good goal, but it mostly holds in the happy path: new tables, a single location, and exclusively relative paths. The moment you introduce operations that rely on absolute references – shallow clones, file imports, tiered storage, or multi-bucket distribution – the zero-rewrite promise starts to crack. What we really want is maximum portability: the ability to move or restructure a table across any distribution topology with the fewest possible metadata changes. No matter what shape a table is already in, relocation should remain simple, fast, and predictable.

Reasoning about file prefixes is hard

The formats ended up with a hybrid approach where some paths are relative and others are absolute. This makes reasoning about path resolution more complex, and increases the surface area for edge cases during migration. Credentials vending is a good example: even if an API (like the Iceberg REST Catalog) can vend credentials for multiple locations, doing it well is difficult because the system has to discover and track all distinct file prefixes across hundreds of millions of file entries in the manifests. And without format-level hints, it’s hard to attach clear operational meaning to those prefixes – or manage them reliably at scale.

Lance: A New Foundation

When I joined LanceDB to work on Lance, it finally felt like we had the right foundation to design from a cleaner foundation. Lance already had two key properties that other formats lacked, listed below.

Predictability over Flexibility

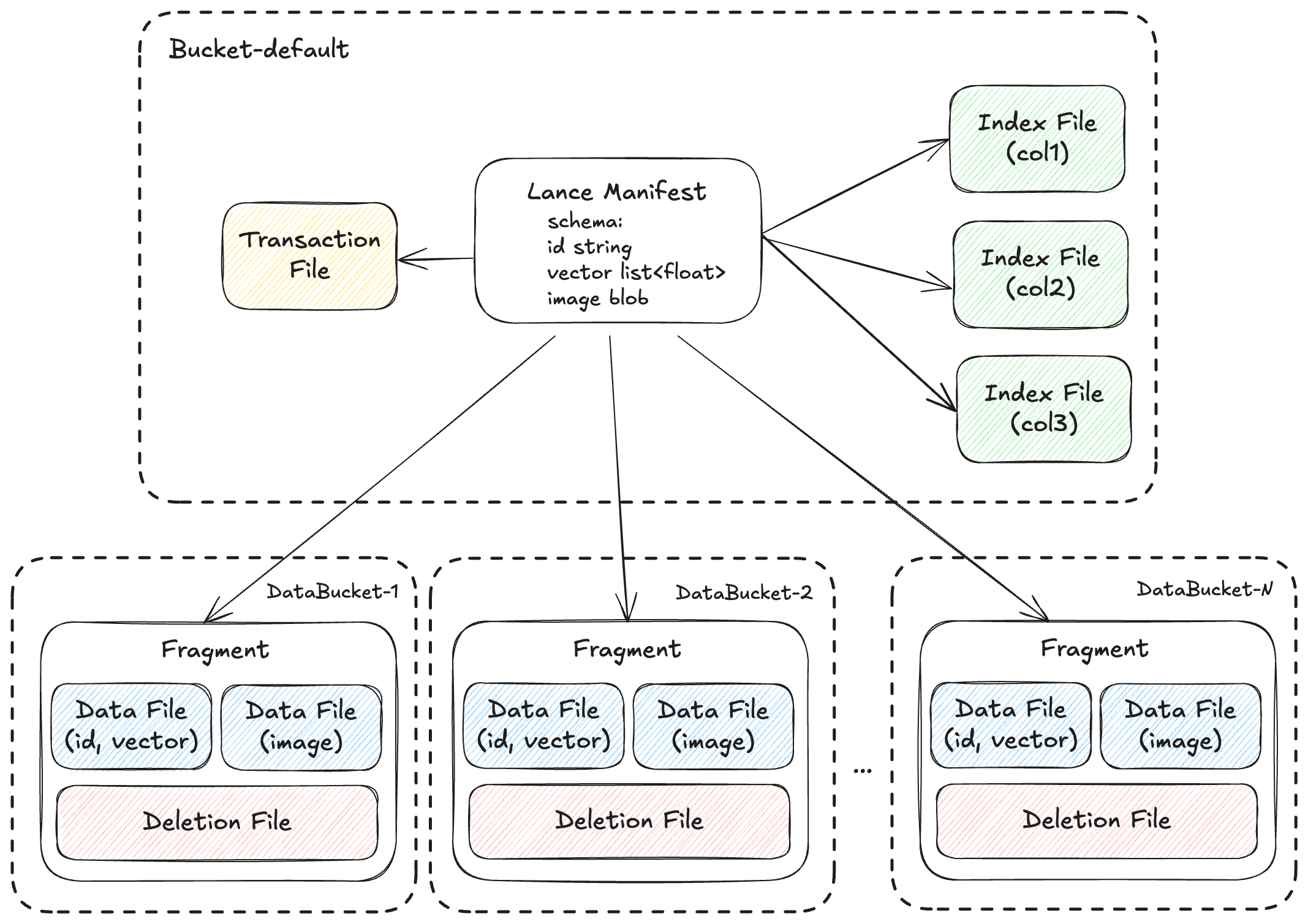

Lance prioritizes predictability rather than flexibility: all files live within a known directory structure, with fixed paths used where possible to minimize manifest size and make path resolution deterministic. Every subdirectory (data/, _versions/, _transactions/, etc.) is defined as part of the format specification.

There is no ambiguity about where files should live.

{dataset_root}/

data/

*.lance -- Data files containing column data

_versions/

*.manifest -- Manifest files (one per version)

_transactions/

*.txn -- Transaction files for commit coordination

_deletions/

*.arrow -- Deletion vector files (arrow format)

*.bin -- Deletion vector files (bitmap format)

_indices/

{UUID}/

... -- Index content (different for each index type)

Strict Portability

Every path in Lance is relative. A dataset can be copied as shown below and it works immediately – no metadata updates required.

cp -r /local/dataset s3://bucket/datasetThis was a deliberate design choice, driven by the needs of Lance users building AI workflows. AI engineers constantly move data between environments: exploring datasets locally, experimenting with transformations, pushing to cloud storage for distributed training and pulling results back for analysis. This iteration cycle happens on a near-daily basis. A table format that requires expensive rewrites for every move would be a non-starter.

With these two properties in place, the direction was clear. Instead of trying to bolt absolute paths onto Lance, we reframed the problem: “how can we keep paths relative, yet still let a single table span multiple storage locations – without sacrificing maximum portability?”

The Uber Use Case

When Uber’s AI infrastructure team brought us a real production requirement, it became the perfect opportunity to validate Lance’s design principles under real-world pressure.

The need came from their multimodal AI workloads: horizontal bucket distribution to scale throughput. The goal was to distribute a single Lance dataset across multiple buckets – so writes spread across them and reads can fan out in parallel.

At petabyte scale, with thousands of concurrent readers accessing the data during model training and agentic search, a single bucket quickly would become a bottleneck. Uber’s goal was to distribute one dataset across N buckets, effectively multiplying aggregate throughput by N.

Writes round-robin across the set of data buckets: as new data is appended, the system cycles through bucket‑1, bucket‑2, …, bucket‑N to distribute files evenly. Reads then fan out across all buckets in parallel. The challenge was representing this in the table format with minimal disruption to existing Lance features. With absolute paths, portability suffers; with purely relative paths, you can’t reference files outside the dataset root. Uber needed both: multi-location storage with maximum portability.

Lance’s Multi-Base Layout Specification

Uber’s use case gave us the opportunity to design something more complete than the status quo. Rather than patching in a one-off solution, we wanted to address a broader gap in open table formats and move toward a principled model for multi-location storage. The missing concept was a location base.

In practice, when a table contains absolute paths, those paths almost always share a small number of common prefixes. Whether the source is file import, shallow clone, or multi-bucket distribution, the number of distinct “bases” stays small—even when the table references millions of files. By making that shared base explicit in the format, and letting file references point to a base plus a relative path, the rest of the design falls into place:

- Controlled flexibility: You get multiple locations for a table, but with explicit structure. No more scanning millions of file paths to discover what locations exist.

- Maximum portability: When you need to port or restructure a table, you update the base paths, not every file reference. Distributing a dataset with 10 million files across 5 buckets means changing 5 strings, not 10 million of them.

- Composable portability: You choose which bases to relocate together. Keep the primary dataset portable while external references point to their original locations, or migrate everything at once, or anything in between.

- Operational clarity: The bases of a table are explicit in the manifest. Features like garbage collection and credentials vending become straightforward: iterate the base paths, not the file list.

Format Specification Details

At table format specification level, Lance manifests now contain an array of BasePath entries:

message Manifest {

repeated BasePath base_paths = 18;

// ...

}

message BasePath {

uint32 id = 1;

optional string name = 2;

bool is_dataset_root = 3;

string path = 4;

}The is_dataset_root field determines path resolution behavior. When true, the base path is treated as a Lance dataset root with standard subdirectories (data/, _deletions/, _indices/). Resolving a data file under this path would mean to add data/ to the base, and then the data file relative path. When false, the base path points directly to a file directory without subdirectories. This distinction enables two use cases: referencing complete datasets (for use cases like shallow clones) and referencing raw storage locations (for multi-bucket distribution like Uber’s setup).

Each file references its base via a base_id, for example:

message DataFile {

string path = 1; // Relative path within the base

optional uint32 base_id = 7; // Reference to BasePath entry

// ...

}

message DeletionFile {

optional uint32 base_id = 7;

// ...

}One important additional benefit to call out in this design is its storage efficiency compared to storing absolute paths. Each base path absolute URI appears exactly once in the base_paths array, regardless of how many files reference that location. Individual files store only a small integer base_id (1 byte for up to 128 bases in protobuf varint encoding) instead of repeating the shared path prefix. This ensures the table manifest is small and continue to be efficient to load in a multi-base situation.

Uber’s Multi-Bucket Lance Dataset

Here’s what Uber’s multi-bucket setup looks like with this design:

s3://bucket-1/dataset_root/ (primary dataset root; is_dataset_root: true)

├── data/

│ ├── fragment-0.lance

│ └── fragment-1.lance

├── _versions/

│ └── 1.manifest (contains `base_paths`)

└── …

s3://bucket-2/ (data bucket; base id: 1; is_dataset_root: false)

├── fragment-2.lance

└── fragment-3.lance

s3://bucket-3/ (data bucket; base id: 2; is_dataset_root: false)

├── fragment-4.lance

└── fragment-5.lance

The primary dataset root in bucket-1 keeps Lance’s standard directory layout and versioned manifests. The additional buckets (bucket-2, bucket-3) hold only data files, with no Lance subdirectories. All locations are registered in the manifest’s base_paths, and each fragment points to its storage location via a base_id.

Working with a Multi-Base Lance Dataset

To make this more concrete, let’s look at a Python example showing how to create and write to a multi-base dataset:

import lance

from lance import DatasetBasePath

import pandas as pd

# Create a dataset with multiple data buckets

data = pd.DataFrame({"id": range(1000), "value": range(1000)})

dataset = lance.write_dataset(

data,

"s3://bucket-1/my_dataset",

mode="create",

initial_bases=[

# Register additional bases for the dataset that will be created

DatasetBasePath("s3://bucket-2", name="bucket2"),

DatasetBasePath("s3://bucket-3", name="bucket3"),

],

target_bases=["bucket2"], # Write this particular batch to bucket2

)

# Append more data

# Write this batch to bucket2 and bucket3

more_data = pd.DataFrame({"id": range(1000, 2000), "value": range(1000, 2000)})

dataset = lance.write_dataset(

more_data,

dataset,

mode="append",

target_bases=["bucket2", "bucket3"],

# Add a new base

dataset.add_bases([

DatasetBasePath("s3://bucket-4", name="bucket4")

])

# Write to the newly added base

new_data = pd.DataFrame({"id": range(2000, 3000), "value": range(2000, 3000)})

dataset = lance.write_dataset(

new_data,

dataset,

mode="append",

target_bases=["bucket4"],

)

# Reading is transparent - just open the dataset

dataset = lance.dataset("s3://bucket-1/my_dataset")

print(dataset.to_table()) # All 3000 rows, from all bucketsThe target_bases parameter controls where new data files are written.

When there are multiple bases, all bases are used in a round-robin fashion.

Reads automatically span all registered bases.

Unlocking New Use Cases

Once we met Uber’s requirements, it became clear that this design enables far more than multi-bucket throughput scaling. Many of the capabilities it unlocks – tiered storage, multi-region layouts, selective failover, and shallow clones – have traditionally required proprietary systems and significant infrastructure. By making multi-base a first-class concept in the open table format, these features become much simpler to build and operate.

Hot-tiering with high-performance AI storage

AI training clusters often pair cloud object storage with high-performance systems such as parallel file systems (e.g., Lustre) or specialized AI object stores (Weka, Nebius, CoreWeave). These tiers can deliver much higher throughput and lower latency for GPU training, but they live at different locations than your primary cloud bucket.

Multi-base makes it straightforward to stage “hot” fragments onto these fast tiers and switch storage backends without changing the table’s structure. You can copy frequently accessed fragments to the high-performance system, register that location as a base path, and let training jobs read hot data from the fast tier while cold data stays in cost-effective object storage.

base_paths:

[

{ id: 1, is_dataset_root: false, path: "/mnt/lustre/training-data" },

]

Multi-region distribution for localized AI training

Global AI deployments need data close to compute. Training clusters in different regions should read from local storage to maximize GPU utilization, and inference endpoints need low-latency access to embedding data for real-time serving. Traditional approaches often rely on complex replication pipelines or vendor-managed multi-region systems.

With multi-base, a single dataset can span regions natively. Training jobs in us-east read from us-east storage, while inference services in eu-west query eu-west replicas. You avoid cross-region transfers on the hot path, minimize operational overhead, and keep data access aligned with where compute runs.

base_paths:

[

{ id: 1, is_dataset_root: false, path: "s3://eu-west-bucket/dataset-data" },

{ id: 2, is_dataset_root: false, path: "s3://us-east-bucket/dataset-data" }

]

Efficient disaster recovery for localized AI serving

Disaster recovery is critical for AI serving at the edge. If data in a region becomes unavailable, semantic search quality and agent performance can degrade immediately, impacting end-user experience. Fast failover to a healthy replica in an available region is essential.

For datasets stored in a single default location, Lance’s relative paths already provide simple disaster recovery: replicate the dataset and open it from the backup location.

Multi-base extends that simple approach to multi-location datasets. When a table spans several bases, you can fail over each base independently. If one region goes down, you update only the affected base path to point to its replica, while the other bases continue serving from their original locations.

# Before: data spread across us-east and eu-west

base_paths:

[

{ id: 1, is_dataset_root: false, path: "s3://us-east-bucket/data" },

{ id: 2, is_dataset_root: false, path: "s3://eu-west-bucket/data" }

]

# After us-east failure: fail over only the affected base

base_paths:

[

{ id: 1, is_dataset_root: false, path: "s3://us-west-backup/data" }, // failed over

{ id: 2, is_dataset_root: false, path: "s3://eu-west-bucket/data" } // unchanged

]

This selective failover means faster recovery and less data movement compared to failing over an entire dataset.

Shallow clone, branching and tagging for AI experimentation

Multi-base also serves as a key foundational building block for Lance shallow clone, branching and tagging, a feature that many ML and AI engineers love for their experimentation workflows.

For example, a shallow clone references data from a source dataset via a base path while maintaining its own modifications. The clone can append data, modify schemas, or delete rows independently. Only the manifest and new data files exist in the clone location; the source dataset remains unchanged:

# Clone at s3://experiments/test-variant references source dataset

base_paths:

[

{ id: 1, is_dataset_root: true, path: "s3://production/main-dataset", name: "source" }

]There’s a lot more to unpack around shallow clone, branching, and tagging: versioned references, clone-of-clone chains, git-like semantics, and more. Stay tuned for a dedicated post on these topics!

Acknowledgments

This work wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the Uber AI Infrastructure team, who provided feedback, helped implement the features in Lance, and validated them at production scale. Special thanks to Jay Narale , who drove the implementation across Rust, Python, and Java, along with comprehensive testing for concurrent writes, conflict resolution, and edge cases.

This collaboration is a great example of how format evolution should work: real production requirements for modern AI workloads shaping the specification, backed by robust implementations that prove the design in practice.

References: