Modern AI-native data infrastructure is no longer about just storing text, metadata, embeddings and pointers to JPEGs – it’s about storage engines that natively support the diverse structures, access patterns, and use cases of complex data seen in practice. A robust data retrieval layer involves far more than just indexing text and running filtered SQL queries. Whether it’s an e-commerce site filtering data by its image catalog, or a financial organization deriving insights from PDFs, or a media firm managing its data for search and content generation (images, video and audio), multimodality is a pragmatic reality of modern AI.

The multimodal reality check

Before diving into the nuances of the term “multimodal”, we must address this question we often hear in the wild: “Why bother with multimodal? Can’t I just generate embeddings and be done with it for my AI application?”

Embeddings are useful tools for similarity search, but they’re lossy representations of data. Real-world systems still need to retrieve, govern, and version the source-of-truth bytes: the actual image, video segment, audio clip, or text spans that a human (or an agent) uses downstream.

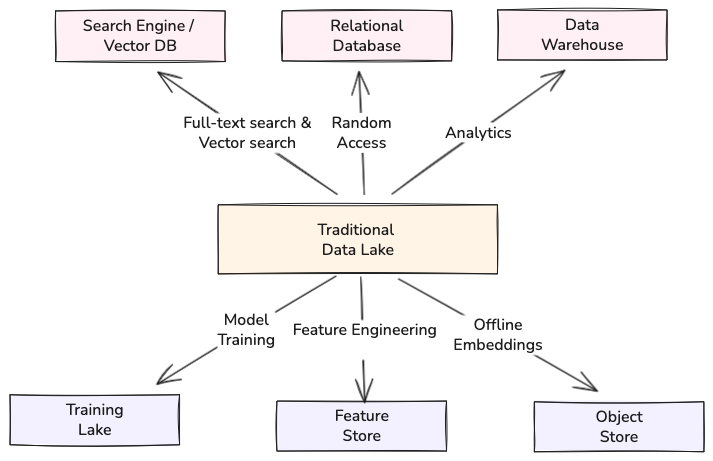

The conventional pattern for handling multimodal data is “store scalar fields and pointers (URLs) in one table, and store the blobs separately in the object store”. Over time, this architecture fragments your mental model: structured fields live in one system, vectors in another, and the bytes somewhere else – all held together by a catalog of pointer URLs and brittle ETL jobs.

As the volume and variety of data, modalities and derived artifacts grow with time (images, PDFs, audio/video, embeddings, captions, labels), traditional architectures often lead to governance drift: deleted files, invalid pointers, stale embeddings, and unclear lineage of what changed when. The usual response is more ETL and more glue code to keep everything coherent, plus more IOPS at runtime (multiple network hops just to serve one “result” back to an application or agent).

A more useful definition of the term “multimodal”

Most people encounter the term “multimodal” as a content-based definition, i.e., what format the data is in – text, images, audio, video, PDFs, sensor logs, and so on. That’s a useful starting point, but it’s not the whole story. In real systems, multimodality also shows up in how that data is accessed (scans vs. random access, online vs. batch) and in how it’s used downstream (analytics, search, feature engineering, training).

In this section, we break down these dimensions of multimodal complexity.

How the data looks

Multimodal data in the wild is often complex, heterogeneous, and nested. Even “simple” image/video datasets tend to mix standard scalar fields alongside high-dimensional vectors and large media blobs. In OpenVid-1M, for example, a single record might include a video_path and caption (strings), a handful of quality and motion scores (floats), an embedding vector (a fixed-size list), and a nested video_blob struct that points at the raw video bytes. Any given row is already a bundle of different shapes and sizes – some scalar, some nested, others large blobs.

This scenario shows up in how the open source video dataset, OpenVid-1M, is distributed: tabular metadata lives in standard files, while the actual videos are shipped as separate archives/blobs and joined back via paths or offsets.

├── nkp37/OpenVid-1M

├── data

│ └── train/

│ ├── OpenVid-1M.csv

│ └── OpenVidHD.csv

├── OpenVid_part0.zip

├── OpenVid_part1.zip

├── ... # Zip files

├── OpenVidHD/

│ ├── OpenVidHD.json

│ ├── OpenVidHD_part_1.zip

│ ├── OpenVidHD_part_2.zip

│ └── ... # Zip filesIn traditional table formats, mixed-width columns (scalar data + large blobs) force a compromise – for reasons of partitioning and performance, you split the “fast” scalar data into a table that’s queryable in SQL, and banish the embeddings and blobs (large binaries) to a separate table or system. Large binary blobs (large video, audio or image bytes), tend to be managed separately in object stores, with pointer URLs in the scalar data table. “Offline” embeddings that are generated via a batch job are stored in feature stores or object stores, and “online” embeddings are maintained in a dedicated vector database, in-memory index, or key-value store.

This is the first dimension of multimodal complexity: it’s not just that you have multiple formats and data structures to store on disk, but that it takes a lot of time and energy to manage the data across different storage layers and multiple systems, while keeping everything in sync with the source data.

How the data is accessed

Even when you keep everything in sync, multimodal workloads introduce a second (and often underappreciated) source of complexity: the way you need to access the data changes dramatically across the AI lifecycle. This is less about where the bytes live and more about the competing I/O patterns your system has to serve. The same dataset gets touched by two very different access patterns:

-

Sequential scans (throughput-oriented): When you’re doing analytics or exploratory work, you want bandwidth. You might scan millions of rows to compute simple statistics (“average brightness across 1M frames”, “distribution of clip lengths”, “how often does this label appear?”), and you want the storage layer to read data efficiently and apply filters quickly. This is the world of high-throughput reads and large, contiguous scans.

-

Random access (latency- and IOPS-oriented): In real-time retrieval and agentic workflows, you want the opposite: small, targeted reads with low latency. You’re rarely reading “a lot of data at once” – you’re trying to find the most relevant items fast, and then you often need to fetch the original bytes (the image, the audio segment, the PDF page, the video frames) to ground a response or power a downstream tool.

What makes these multimodal access patterns especially tricky is that real workflows often combine both personalities of data in a single request. For example, you might want to isolate frames of “outdoor scenes in broad daylight with city landscapes”. A common pipeline is: find candidate frames via embeddings and semantic search (random access), apply additional filters (sometimes scan-like, sometimes point lookups), and then fetch the raw frames for downstream use.

Training pipelines also bring a mix of scan and random access pressure. Each epoch needs fresh, random batches of examples, requiring efficient shuffles (random access). If your storage engine is only good at scans, the data loader ends up doing lots of small, scattered reads – and if those reads also require multiple network hops (first to fetch IDs or embeddings, then to fetch the raw bytes from an object store), IOPS saturate quickly. This dichotomy leads to ML teams maintaining lots of custom infrastructure and caching layers to balance IOPS such that their GPUs are sufficiently fed, adding significant costs over time.

This is the second dimension of multimodal complexity: you don’t just need a place to store the data – you need a retrieval layer that can serve both high-throughput scans and low-latency random access, from the same source of truth, without forcing you to build and maintain multiple “performance copies” of the same dataset across different systems.

How the data is used

If the previous dimension of multimodal complexity was how you access the data, this one is about why you’re accessing it in the first place. Enterprise data isn’t a static artifact you “load once and query forever”. It’s a living, breathing asset that gets reused, reinterpreted, and enriched over time – often by people with very different goals and mental models.

The same underlying video collection (or robotics dataset, or PDF archive) might need to support all of the following (sometimes in the same week!):

- The data scientist (EDA and dataset sanity checks): They’re trying to understand what’s in the data before they trust it. They ask questions like “Do we have class imbalance?”, “Which scenes are underrepresented?”, or “Show me frames that look like a pedestrian in the middle of the road.” These are ad-hoc, iterative queries that mix filters, sampling, and pulling back raw examples to inspect.

- The analyst (metrics and reporting): They care about longitudinal trends and aggregates. “How many red-light incidents happened last month?”, “What’s the distribution of near-miss events by region?”, “How did the model’s false positive rate change after the last release?” These are scan-heavy workloads that need consistent semantics and reproducible results.

- The application developer (search and product experiences): They’re building interactive features: “search by image”, “find similar clips”, “retrieve the most relevant PDF pages”, “show related products”. Latency matters, and the application needs both the retrieved context (metadata) and the retrieved content (pixels, audio, page crops).

- The ML engineer (feature engineering and labeling loops): They want to run pipelines that generate new/derived columns (e.g., captions, tags, OCR output, embeddings, quality scores) and write them back, often repeatedly, as models improve. The dataset evolves, but it still has to remain queryable and consistent for everyone else.

- The training/infrastructure team (large-scale training and evaluation): They’re pulling massive subsets of the data for training foundation models, doing repeated evaluations, and slicing performance by metadata. They need high throughput (scan performance) to gulp large batches of data for their GPU clusters, but they also need fast random access, to isolate the most relevant subsets of the data and to ensure randomized samples via shuffling.

- The agent (tool-using retrieval and action): Increasingly, the “user” is an agent that chains retrieval with downstream tools and workflows. It doesn’t just use “nearest neighbors” – it requires the source-of-truth bytes (the image, the relevant video segment, the specific PDF page) to stay grounded while it reasons and acts.

This is the third dimension of multimodal data in the enterprise: the same data must serve a wide range of downstream consumption scenarios, across multiple personas, without forcing you to copy, reshape, and migrate your dataset into different systems every time the question changes.

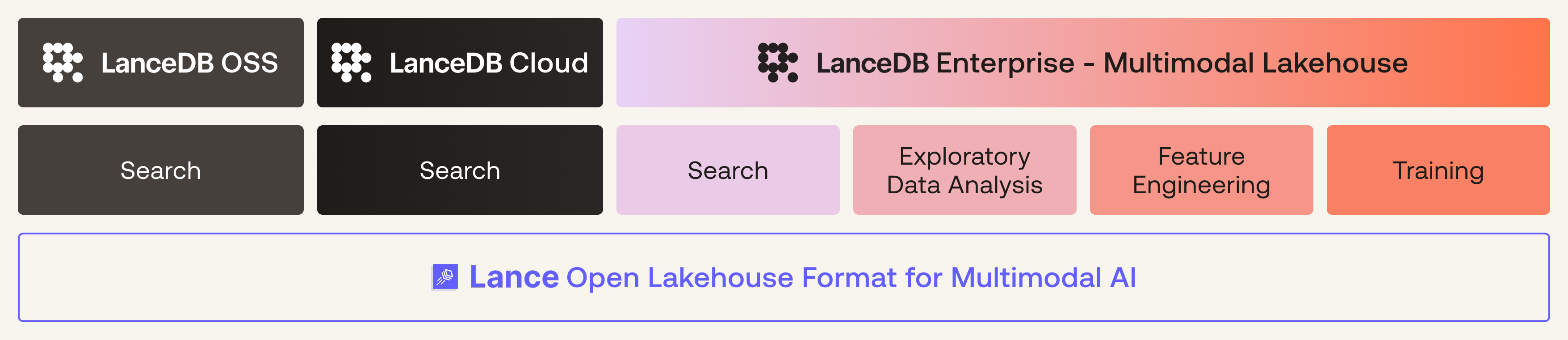

Why we built LanceDB

LanceDB’s multimodal lakehouse is built on top of the open source Lance format, designed to address the challenges of managing multimodal complexity we just walked through. In LanceDB, the same table can function as a lakehouse table when you’re scanning and transforming data, and like a low-latency retrieval system when you’re serving search and agentic applications.

1. Single source of truth, for all your data

The first premise is straightforward: stop treating your raw bytes as second-class citizens. LanceDB uses Lance tables under the hood: a Lance table can natively store not only standard tabular columns, deeply nested structures, and embeddings, but also large binary blobs (images, video and/or audio) alongside traditional tabular data. That means the content can stay physically co-located with the context, instead of being scattered across a relational database, a vector store, and an object store full of opaque files.

Here’s how the structure for several terabytes of video data from the OpenVid-1M would look with Lance: it’s just a collection of Lance files that include the video embeddings and binaries in one place.

├── lance-format/openvid-lance

├── data

│ └── train/

│ ├── 0001.lance

│ ├── 0002.lance

│ └── ... # more Lance filesLance , an open lakehouse format, makes this kind of storage practical with its file format and table layout. Rows are grouped into fragments, where each fragment can have multiple data files that hold one or more columns. This two-dimensional layout matters in multimodal settings because it lets the dataset evolve without constantly rewriting the heavy parts. If you add a new embedding column, run OCR on PDFs, generate captions, or attach new labels, Lance can write those new columns as additional data files per fragment – without rewriting the existing image/video bytes you already stored.

Just as importantly, Lance tables are versioned. Each commit produces a new table version (tracked via manifests), which gives you a stable snapshot to reproduce training runs, debug “what changed?”, and avoid the silent drift that happens when pointers, blobs, and embeddings evolve out of sync.

The result of this is simplified data governance with fewer unnecessary IOPs, with performance and scalability guarantees baked in.

2. Supports online and batch workloads

The second premise directly addresses the “split personality” problem of access patterns. A Lance table is specified by a columnar file format, so just like other columnar formats, it can deliver high-throughput scans (with column pruning) for analytics and filtered queries. But unlike traditional columnar formats that essentially optimize for “scan-is-all-you-need” use cases, Lance is designed to be the fastest format for random access, without compromising scan performance. In the Lance format (and LanceDB above it), indexes aren’t an afterthought: they’re stored alongside the data (using pointers in the Lance manifest), and the system can use them to avoid read amplification when you only need a small slice of a massive dataset.

Practically, these design decisions are what make LanceDB a “one dataset, many workloads” solution for multimodal data in the enterprise. You can use the same table in a batch pipeline (scan, filter, compute new columns, write them back) and then immediately serve low-latency queries against the enriched data – without exporting to a separate online store. And because Lance “ speaks Arrow ”, the same dataset can be consumed by tools that understand Arrow datasets (e.g., DuckDB, Polars, DataFusion), making it highly versatile for a variety of stacks.

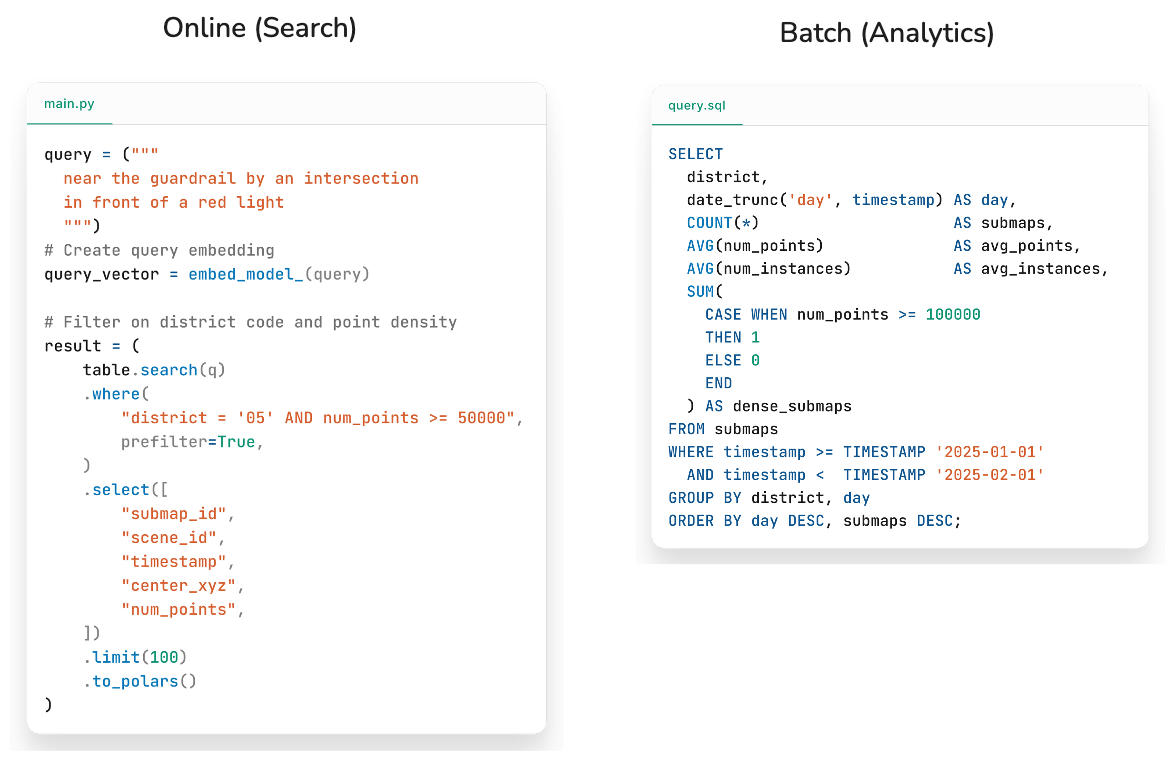

Below is an example of two different access patterns in an autonomous vehicle dataset. The first one shows an online scenario you may want to search, explore and isolate (in real time) a small subset of scenes that align with a query in vector space. The second one shows how that same data, at a different point in time, may be used to run a batch SQL query (which LanceDB supports via the Arrow FlightSQL protocol , or via DuckDB using the lance-duckdb extension) for a month-end report.

3. Far more than just search

The third design premise is all about scope: LanceDB is not just “a vector database plus a storage format”. It’s a complete solution built for the reality that search is only one part of the lifecycle, and that the boundary between “retrieval” and “data processing” gets blurry in multimodal systems.

Search is only a part of the variety of workloads seen in the enterprise. It’s common to see teams building and iterating on datasets, by first looking up small, meaningful slices to understand the data, and then enriching the data via feature engineering, labeling or captioning, and transforming existing or derived columns (embeddings, captions, OCR outputs, quality scores) for downstream applications. This new data can also be used as training data for foundation or fine-tuned models that can further empower agents. All these aspects govern the mechanics of how messy multimodal bytes are turned into a dataset your organization can actually trust and reuse.

This is also where the Lance format’s role matters. Lance is a file format and a table format with a built-in notion of versioned datasets (manifests, fragments, and snapshots), acting like a lightweight catalog for how your data evolves over time. Instead of relying on a separate catalog plus a maze of pipelines to infer “what version of the data is this?”, or “where is the latest source data for these embeddings located?”, the table itself carries that history forward. This means you can reproduce a training run, roll back a bad data enrichment job, and confidently iterate on your data model as your source data and use cases evolve.

In practice, this is what makes up LanceDB: an OSS and enterprise product that helps teams run search, analytics, feature engineering, and training, all on the same underlying data, no matter its size or shape. Fast data evolution (adding and rewriting columns without rewriting the whole dataset) and first-class indexes (vector, full-text search, and scalar) keep the dataset usable as it changes, without duplicating data across systems or rebuilding brittle pipelines every time you switch workloads.

Rethinking what “multimodal” means for AI

The main takeaway from this post is that the term “multimodal” is not just a content label (text vs. images vs. audio) – it’s a property of your system: how you store and version raw bytes, how you serve competing access patterns, and how you keep a dataset usable as different teams (and different applications) reuse it over time.

This shift in perspective matters because as AI agents become more and more widespread, the ecosystem’s needs are rapidly moving from “generate an answer” to “act in an environment”. An agent fluent in natural language can still be ungrounded if it can’t reliably retrieve and interpret the underlying pixels, pages, clips, and sensor traces that make up reality.

“LLMs transformed how we access and work with abstract knowledge. Yet they remain wordsmiths in the dark – eloquent but inexperienced, knowledgeable but ungrounded. Of all the aspects of intelligence, visual intelligence is a cornerstone of intelligence for animals and humans. The pixel world is so rich and mathematically infinite.”

– Fei-Fei Li, CEO of World Labs and Professor of Computer Science at Stanford

So as multimodal AI continues to proliferate across industries, the right question to ask yourself isn’t “Do I have multimodal data?”, but rather: “How should I store, query, and persist my data effectively to handle the full spectrum of use cases and workloads in my organization?”

We believe that true multimodal infrastructure for AI shouldn’t require you to be a distributed systems expert or have an army of data engineers just to get your data to the teams that need it. We built LanceDB, the Multimodal Lakehouse , a unified system where images, videos, embeddings, metadata (and more) live together – queryable by SQL, searchable via embeddings, and available for training and inference at petabyte scale.

The future of AI infrastructure lies in architectures that embrace these aspects of multimodal complexity – without forcing you to fragment your data, duplicate your pipelines, or compromise on performance.